- Home

- Kate Davies

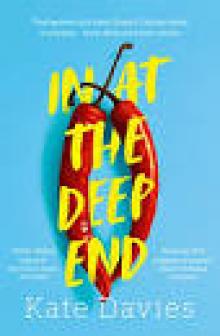

In at the Deep End Page 2

In at the Deep End Read online

Page 2

‘OK,’ said the GP. ‘It’s unlikely that you have clinical depression.’

‘Hooray!’ I said, giving myself a little cheer.

The GP smiled again – a patient smile, I now realize, looking back on it. ‘You appear to have what we call Generalized Anxiety Disorder,’ she told me.

I was very excited to have an actual disorder.

‘I’ll refer you for talking therapy,’ she said. ‘But it might be better to go private – the NHS waiting list is nine months long.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘The Department of Health and Social Care gets a lot of letters complaining about that.’

I felt calmer than I had in ages. I went home and Googled cheap counsellor north London anxiety, and Nicky’s name came up. She was still training to be a therapist, which is why I could afford her, and she had an un-therapist-like way of voicing her very strong opinions on almost every topic. When I told her about the anxiety, and about feeling lost and directionless in life, she said it was no wonder I was anxious, and that my job sounded so dull they should ‘prescribe it to insomniacs’.

Anyway, I told Nicky about the wank. I could feel myself sinking deeper and deeper into the armchair as I spoke, as though it was recoiling from me. She didn’t recoil, though. She wanted to know all about it.

‘What did the couple look like?’

‘Does that matter?’

‘I don’t know until you tell me.’

‘She was overweight and black. He was skinny and white.’

‘Aha.’ She nodded in a therapist-like way.

‘What?’

‘Nothing.’ She scribbled something in her notebook and underlined it several times.

‘Do you often masturbate thinking about Alice?’ she continued.

‘I wasn’t thinking about her!’

‘But you said you were wanking out of resentment.’

‘I was pissed off with them for having such loud sex, that’s all.’

‘Because you’re not getting any?’ She gazed at me, unblinking.

‘Look, I’m not repressed, all right? I’d have sex if anyone wanted to have sex with me, but no one has for ages.’

‘So you’re just waiting for someone to offer it to you on a plate.’

‘Well, no—’

‘That’s what it sounds like to me. It’s just like your career. You’ve just decided to sit back and stay in this dead-end temp job—’

‘I’m a contractor, actually, not a temp. And I might apply for the Fast Stream this year,’ I said.

‘Why didn’t you apply last year?’

I hadn’t applied because that would mean saying ‘I’m a civil servant’ when people at parties asked, ‘What do you do?’ and then having to answer a lot of questions about NHS funding and whether I approve of the government. I hate it when people ask, ‘What do you do?’ I assume everyone does, even if the answer is ‘I’m a novelist,’ or ‘I’m a surgeon specialising in babies’ hands,’ because even then you know someone will say, ‘Will you show my book to your agent?’ or ‘Can you look at this lump on my finger?’ I missed being able to say, ‘I’m a dancer.’

I looked at the floor. There was some sort of stain on the carpet – ketchup, possibly.

‘You need to make an effort with your career,’ Nicky said. ‘It’s the same as your love life. You’re not prepared to put yourself out there.’

‘I’m not going to go looking for a relationship. I don’t need one to make me complete. I’m independent.’

She put down her notebook. ‘Are you independent?’ she asked. ‘Or are you really, really sad?’

I maintained a dignified silence.

‘It’s OK to cry,’ she said.

‘I’m not that sad,’ I said.

‘Just let it out.’

‘I’m not crying,’ I said, which wasn’t strictly true.

She handed me the tissue box triumphantly.

I called Cat on my way home from Nicky’s. I didn’t want to be alone with my thoughts, and I could always rely on Cat to tell me an anecdote about her terrible career to put my problems in perspective.

‘Do you fancy a drink?’ I asked, when she picked up the phone.

‘I wish,’ she said. ‘I’m in Birmingham. Doing the life cycle of the frog again.’ She sounded a little out of breath. She’d probably been having energetic sex too.

‘When are you back?’ I asked, sidestepping a puddle.

‘Not for ages,’ she said. ‘It’s a UK tour.’

‘Ooh!’

‘Of primary schools.’

‘Oh.’

‘I’m probably going to get nits again. Or impetigo.’

Cat couldn’t get work as a dancer after school – every company she auditioned for said, ‘You have the wrong body type,’ which is the legal way of saying ‘You’re black.’ But instead of doing what I did when my dance career ended – moving back in with my parents and swearing never to perform again, except to sing my signature version of ‘I Wanna Dance with Somebody’ at karaoke nights – she retrained as an actor. Now she earned most of her money performing in Theatre in Education shows, playing roles like ‘frog’ and ‘plastic bottle that won’t disintegrate’ and ‘uncomfortably warm polar bear’. I think we probably stayed close over the years because neither of us could stand our other friends from dance school, with their OMG I just got cast in Birmingham Royal Ballet’s Swan Lake! #Blessed Instagram posts. I did feel envious of Cat sometimes, though. She still got to experience the thrill of applause, even though the people applauding sometimes pulled each other’s hair and had to be sent to the naughty corner.

‘Lacey’s playing the frogspawn,’ Cat continued, ‘and she won’t stop going on about the musical she’s writing about periods.’

‘I bet that’s actually going to be really successful,’ I said.

‘It is, isn’t it? Oh God …’

I heard a muffled sort of stretching sound on the other end of the line.

‘Are you taking your tadpole costume off?’ I asked her. ‘Go on, sing me the tadpole song again.’

‘I’m the frog this time. Fucking green leotard is a size too small.’

‘You’ve been promoted!’

‘Very funny,’ said Cat. ‘One of the kids came up to me today and said, “You’re not a real frog. You’re too big.” I swear six-year-olds are getting stupider.’ More stretching and shuffling, and then a grunt of effort. ‘Got it off.’

‘So now you’re naked.’

‘Yep. This is basically phone sex,’ she said.

‘This is the closest I’ve come to a shag in three years.’ I gave myself a mental pat on the back. At least I could joke about it.

‘I thought I had it bad,’ Cat said. ‘Lacey’s been shagging Steve, the new tadpole, all tour, and I’ve been feeling like a total third wheel.’

‘You’re best off out of that,’ I said. ‘Tadpoles shagging frogspawn is all wrong. Sort of like incest.’ I tucked my phone under my chin and unlocked the front door.

‘How are you anyway? How’s work?’ asked Cat.

‘Too boring to talk about.’

‘You need a creative outlet outside work.’

‘No thanks,’ I said. All I wanted to do was watch TV without listening to people have sex. I sat on the sofa, coat still on, and felt around between the cushions for the remote. Come Dine with Me was on, and Alice and Dave were out. This was shaping up to be a good evening.

2. NO-MAN’S-LAND

I was a little late to work the next day, so my usual desk was taken. I waved at Owen, who I usually sit with, across the grey no-man’s-land of desks and chairs. I could feel other people looking up at me from the trenches, so I ducked down into the nearest seat, next to Stan, one of the press officers. I usually try to avoid Stan, because he breathes loudly and eats crisps all day. An unsociable combination. This morning he’d gone for salt and vinegar rather than cheese and onion, which was a blessing.

I couldn’t concentrate on loggi

ng the new emails and letters – my session with Nicky was still playing on my mind – so I pulled out the latest letter from Eric, the Bomber Command vet, written on thin, yellowing lined paper in shaky blue biro, and started drafting my reply.

You’re not supposed to draft a stock response to government correspondence – you’re supposed to treat each letter writer as an individual. There are guidelines that tell you how to address a Baroness (‘Baroness Jones, not Lady Jones; it’s important to distinguish Baronesses from women who become Ladies when their husbands become Sirs’) and how to refuse an invitation to a Minister (‘Unfortunately, pressures on her diary are so great that she must regretfully decline’). Sometimes you take letters to the Minister for their signature. Sometimes, if the letter isn’t addressed to the Minister, you sign it yourself. Some people write back over and over again, so working on the correspondence team is a bit like having lots of self-righteous pen pals. Eric, the Bomber Command veteran, wasn’t self-righteous, though.

The care home staff are under so much pressure that they don’t have as much time to spend with us as they used to. I think the cuts to social care are a crying shame. Older people are an easy target, because once we reach a certain age, we’re hidden away out of sight.

Most of the old dears at my care home don’t get any visitors at all. That just breaks my heart. I’m lucky – I have a daughter who comes and sees me twice a week. She’s very good. But it’s very lonely getting older. I miss Eve, my wife, more than I can tell you. She died four years ago. Have I told you about her already?

Lovely Eric. He reminded me of my granddad, who I missed every day. When I was at university, Granddad had written to me every month or so, in wobbly, old-fashioned handwriting, telling me stories about his allotment and his cats, always slipping a ten-pound note into the envelope. I had usually been too busy getting drunk to write back. So I took extra care with my letters to Eric. I typed out the old lines about difficult choices and austerity, and then I asked him to tell me more about his wife, because I knew what it was like to be lonely. I caught myself thinking: At least he had a wife. And then I realized that being envious of a bereaved care home resident was taking self-pity too far, and decided to pull myself together.

I finished my letter and I was wrangling with the printer – usually you have to put the headed notepaper in face down, with the letterhead closest to the printer, but someone had fiddled with the settings – when I saw Owen heading to the kitchen for a coffee. I decided to corner him.

I glanced into the hallway to check that no one was about to interrupt our conversation and asked, ‘How long has it been since you had sex?’

Owen spends most nights gaming, and most of his lunch breaks reading comic books, and not a lot of time with members of the opposite sex. So I thought his response to my question would make me feel better. I was wrong.

He glanced at his watch. ‘Two and a half hours.’

‘You had sex this morning?’

‘That’s right.’ Owen crossed his arms and smirked.

‘No need to be so smug about it.’

‘But I am smug!’ said Owen. ‘Do you know how long it had been before I met Laura? Four years.’ He grabbed my arm and gave it a little shake. ‘Over four years. I hadn’t had a shag since I was twenty-four!’

I felt slightly better after that. ‘I haven’t had sex in three years.’

I could see Owen trying to arrange his face into an expression of sympathy. ‘Poor you,’ he said.

‘So. Who’s Laura?’

He shrugged. ‘We’ve been seeing each other for a few weeks.’

‘Great.’ I nodded and smiled, as convincingly as I could.

‘She does roller derby. She has tattoos all over her thighs.’

‘I don’t think I need to hear about her thighs,’ I said, lowering my voice as a group of Fast Streamers walked past the kitchen, speaking to each other in low voices as if they knew something we didn’t, which they undoubtedly did.

‘Sex is great,’ he said, smiling to himself in a way that let me know he was thinking about Laura’s thighs. Or what was between them. Grim. ‘I’d forgotten how good it is.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘Don’t rub it in.’

The sex chat made us late to our team meeting. Owen and I huffed into the glass-walled meeting room, breathless, saying, ‘Sorry, sorry,’ as we sat down.

Tom didn’t look up. He had a very passive aggressive management style – that’s what I’d have liked to say in the annual Staff Engagement Survey, but our team was so small I thought he’d trace the feedback to me and passive-aggressively punish me for it. Probably by making me answer all the correspondence about Brexit.

There were three of us on our immediate team besides Tom: me, Owen and Uzo, who was smiling up at me kindly now. Uzo was always smiling at me kindly. She’d been working on the correspondence team for twenty years and had the least ambition of anyone I’d ever met. Whenever I messed up, she’d say things like, ‘Don’t worry, girl. You won’t care when you’ve worked here as long as me,’ and I’d go and quietly hyperventilate in the toilets. She did have a lovely collection of statement necklaces, though.

‘As I was about to say,’ said Tom, still not looking up, ‘they’re bringing in a new Grade Six.’

Owen and I looked at each other.

‘What, another senior manager?’ said Owen.

‘Yes, Owen,’ said Tom, smiling his tight smile.

‘Above you?’ said Owen.

‘Yes,’ said Tom, his smile tighter still. ‘Above me.’

‘But we thought you were going to be promoted,’ said Owen.

‘Yes, well. So did I,’ said Tom. He fiddled with his tie.

‘Fuck,’ said Uzo, which, to be fair, was what the rest of us were thinking.

‘And I have it on good authority that the new Grade Six is hardline on swearing in the workplace.’

‘Shit,’ said Uzo.

‘That was a joke,’ said Tom.

‘What’s his name?’ asked Uzo.

‘Her name,’ said Tom, ‘is Smriti Laghari. I’m pleased to see you were paying attention during unconscious bias training.’ Sarcasm was another of Tom’s management techniques.

Owen took out his phone and started Googling Smriti. ‘She’s with Private Office at the moment. Used to be a banker.’

Groans from around the table. Former bankers were the worst for trying to make the Civil Service more efficient, which often meant getting rid of people and cutting ‘luxuries’ such as having enough desks for people to sit at.

‘According to LinkedIn, her interests include Cardiff University, Pineapple Dance Studios and the London Amateur Violinists’ Network,’ continued Owen.

‘I can play the cello,’ said Uzo. ‘Maybe we could form a quartet. Ha!’

Tom closed his eyes a moment, as though trying to gather his strength. ‘It’s fine,’ he said. ‘We just need to cut down on the backlog before she gets here. Let’s show her what a brilliant, efficient team we are. Shall we?’

We stared at him. He had never used the words ‘brilliant’ or ‘efficient’ to describe us before. Nor, it’s safe to say, had anyone else.

It was dark by the time I left work. I called my mother as I walked down Victoria Street to the Tube, trying not to slip on the lethal rotten leaves that covered the pavement.

‘It’s me,’ she said, as she picked up.

‘I know,’ I said. ‘I called you.’

‘Oh, sorry. I’m a bit distracted. I’m on the computer, doing the Sainsbury’s shop. They have a very good offer on olive oil, if you need any.’

‘Thanks, Mum,’ I said, imagining her in the lovely warm kitchen in leafy North Oxford, my dad at the table next to her, reading his undergraduates’ essays and grumbling about how badly academics are paid these days. I suddenly wanted to be there with them. ‘How are you?’

‘Awful, if you must know,’ she said. ‘The neighbours are digging out the basement and doing a loft co

nversion.’

‘Is that a bad thing?’

‘A nightmare. Nothing but dust and banging. And the mess in the street. They’ve thrown away the Victorian doors!’

‘Not the original features!’ I said.

‘Sarcasm doesn’t suit you, Julia,’ she said. ‘The house is going to look ridiculous. And it’s not as if they need more space. There are only four of them! They’re knocking down all the walls downstairs to build an entertainment centre.’

I was approaching a new tower block on the corner of Vauxhall Bridge Road. It looked like a middle finger, mocking me.

‘Sorry, darling,’ said Mum. ‘You caught me at a bad time. They just came round for a chat about the party wall and called our kitchen “quaint”. What can I do for you, anyway?’

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘I’m about to get on the Tube.’

‘Wait, darling. What were you calling to tell me?’

‘Nothing much. Just a new Grade Six joining our unit.’

‘Oh,’ said Mum. ‘What does that mean?’

‘She’s going to be in charge of our department. It sounds like she might want to make things more efficient.’

‘I’m sure you’re very efficient, darling.’

‘No, I’m not. And I’m a contractor, so I’m easy to get rid of.’

‘No one has said anything about you losing your job yet. Have they?’

‘No.’

‘Well then. Anyway, it’s not as though you’re the Health Secretary.’

‘Thanks, Mum.’

‘Come on, darling. You know what I mean. You’re selling yourself short, staying in that job.’

‘I’m not qualified for anything else!’

‘Rubbish! You could train to become a Pilates teacher. Or an osteopath.’

‘You think osteopaths are quacks!’

‘Fine. A barrister then!’

‘Be serious.’

‘You could! You could go to law school!’

‘Who’s going to pay for that?’ I said.

‘Or edit books, like Alice does. You have exactly the same qualifications as her.’

‘Yeah, because that’s a great way to make money. She’s been doing it for five years and she still has “assistant” in her job title.’

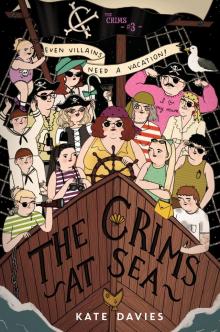

The Crims #3

The Crims #3 In at the Deep End

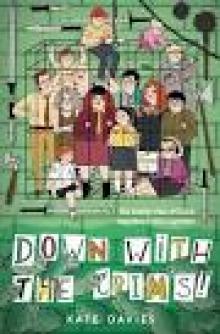

In at the Deep End The Crims #2

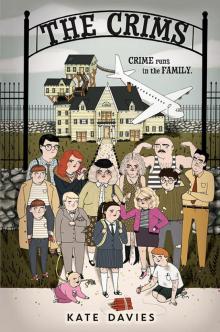

The Crims #2 The Crims

The Crims Take a Chance on Me: Lessons, Book 4

Take a Chance on Me: Lessons, Book 4