- Home

- Kate Davies

The Crims Page 17

The Crims Read online

Page 17

“So he definitely won’t be home this weekend?”

“No,” said Uncle Clyde. And then he straightened up. “Wait a minute,” he said, drumming his fingers thoughtfully on his chin.

Imogen felt hope begin to bubble up inside her again. “Are you thinking what I’m thinking?” she asked Uncle Clyde, a slow smile spreading across her face.

“I think so,” said Uncle Clyde, nodding. “There might be a way to get the lunch box back to the police . . . and humiliate Jack at the same time. . . .”

“SHH! ALL OF you!” hissed Imogen.

This was the moment she had been waiting for.

Any second now, they would pull off the biggest reverse heist in history.

As long as her cousins didn’t spoil the whole thing by coughing and giving them away . . .

She closed her eyes and counted to five, the way Big Nana had taught her to do when things (or her family) got too much. She was hiding in a small wardrobe in a large bedroom in an enormous mansion—Wooster Mansion to be exact. She was squashed up against the Horrible Children, and one of them didn’t smell very good. She suspected it was Henry—he’d drawn the blueprint of the mansion on his stomach the previous Thursday, and he’d refused to have a bath since.

And then suddenly, they all froze—the bedroom door had creaked open. The Horrible Children started jostling for the best view out of the crack in the wardrobe door.

“It’s Jack Wooster’s maid!” hissed Nick (or Nate).

“Shh!” said Imogen again, her heart pounding.

Luckily, the maid hadn’t heard them—she was humming the old Captain Crook theme tune to herself as she started to dust.

The maid was an irritatingly thorough duster, it turned out.

She dusted the bedside table and the wardrobes and every tiny china trinket on the mantelpiece. There were a lot of them.

The Horrible Children were starting to get cramps.

Imogen thought her heart might beat out of her chest.

Finally, the maid moved on to the broken, empty glass cabinet where the lunch box had been displayed before it was stolen; she stopped humming at this point, as a mark of respect. And then—

“AAAAAGHGGHGHGGHHGGH!” screamed the maid.

The Horrible Children jumped and swore at one another and generally made quite a lot of noise inside the wardrobe.

But the maid didn’t notice. She was at the floor beneath the glass cabinet.

Because there, peeking out from behind an umbrella stand, was . . .

The lunch box!

The maid grabbed a phone. “I’VE FOUND IT!” she yelled.

Then she realized she hadn’t dialed a number yet.

She tried again.

As soon as Jack Wooster answered, she shouted, “I’VE FOUND IT! I’VE FOUND THE LUNCH BOX! WHAT DO YOU MEAN WHICH LUNCH BOX? THE CAPTAIN CROOK ONE!”

Imogen felt like she might cry or collapse with relief. She grinned at Delia, which was hard, because her head was pressed up against Sam’s elbow. Delia grinned back, and she reached out to hold Imogen’s hand.

Imogen couldn’t quite believe it. She had actually done it. They had done it—together. She felt purely happy—like she had really achieved something, something really worthwhile, and that everything was right with the world. This was real satisfaction—it was so much more intense than the feeling she got when she came in at the top of the class in a physics test. She hadn’t felt this happy, this excited, for over two years. Since before Big Nana died. Since the last time she had pulled off a brilliant, ingenious crime caper with her brilliant, ingenious family.

“So in conclusion,” said PC Donnelly, standing behind the podium at the press conference a few days later, “the lunch box wasn’t stolen at all. It looks like it was all one big misunderstanding.”

The press groaned. The most exciting news story in the history of Blandington had turned out not to be a news story after all.

“What does Jack Wooster have to say about this?” called a grumpy journalist.

“I’ll tell you what I have to say,” said Jack Wooster, striding up to the podium and pushing PC Donnelly out of the way. “If this is a ‘misunderstanding’”—he made air quotes—“then my name is Clyde Crim. WHICH IT CLEARLY IS NOT. BECAUSE I AM A THOUSAND TIMES THE MAN HE WILL EVER BE. There is CLEAR evidence of Clyde’s ridiculous ‘heist’”—he made air quotes again—“ALL OVER MY MANSION. Would I smash the glass in my own glass display cabinet? Would I dress a greased pig up as a young girl and let it run loose in my own mansion? Would I blow up a bouncy castle in my own back garden? Would I even deign to own something as down-market as a bouncy castle? The answer is NO!”

“Be that as it may,” said PC Donnelly, elbowing his way back to the podium. “Now that the lunch box has been recovered, the Blandington Police Department has no choice but to release the Crims from custody. Immediately.”

The press cheered at this; the Crims being released definitely counted as news. And they cheered even more when the Crims themselves walked into the room. They could always be relied upon to look ridiculous in photographs.

Uncle Clyde walked up to the podium and smiled. “I’ll happily take any questions you have about The Heist and how brilliantly I planned it,” he said to the journalists. “Except from you,” he said, pointing to the grumpy journalist who had spoken earlier. “I don’t like your mustache.”

Hands went up all over the room.

“Yes?” said Uncle Clyde, pointing to a woman at the back of the room. “You, with the face.”

“Do you still plan to carry out The Heist one day?” asked the woman with the face.

“Absolutely!” said Uncle Clyde.

Imogen watched Jack Wooster shoot a look at PC Donnelly. PC Donnelly just shrugged.

“Another question,” said Uncle Clyde. “Yes—you, in the middle, with the arms.”

The man with the arms asked, “Did you think you’d ever get out?”

Uncle Clyde smiled. “I can honestly say that I thought we’d be in prison for the rest of our lives. And we would have been . . . if it hadn’t been for one incredible person.”

He winked at Jack Wooster’s maid, who was sitting in the audience, blushing.

“She’s remarkable—modest, determined, great with a vacuum cleaner . . .”

Jack Wooster’s maid sat up a little taller.

“And she’s my own flesh and blood.”

Jack Wooster’s maid looked a little confused.

“We owe this all to my niece, Imogen Crim . . . the sharpest mind in this family since my legendary mother!”

The journalists burst into applause. The maid burst into tears. And Imogen felt so proud she felt like she might literally burst, but she didn’t, because that would have been messy. Uncle Clyde had actually compared her to Big Nana—and this time, she felt she almost deserved it. When she’d been little, all she had ever wanted was to be as good a criminal as Big Nana—and now she was. She had proved that she was every bit as talented as Big Nana thought she could be. She vowed to memorize Uncle Clyde’s words and think about them whenever she doubted herself. Except the bit about being good with a vacuum cleaner—she had no idea what that was about.

Imogen smiled as she looked around the room. Her eyes rested on her father, who was sitting quietly on a chair on his own, polishing his glasses and beaming in her general direction (he really was quite blind when he wasn’t wearing them). She rushed over to give him a hug.

“Imogen,” he said, grasping her hands. “I’m so proud of you. And grateful. Finally, I get to use a calculator again, and it’s thanks to you.”

“You’re welcome, Dad,” Imogen said. Everything had been worth it to see the smile on his face.

He nodded, a bit of sadness creeping into his eyes. “And for you . . . It’s back to school, isn’t it? I’m sure you can’t wait to get back to all the great things you were doing there. Will you come home this summer, do you think?”

“I’m not sure

,” said Imogen. She was having trouble picturing the summer. She was having trouble picturing herself at Lilyworth, too, although surely that was temporary. “I can’t wait to go back,” she said, trying to sound confident.

She and her father sat in silence for a while, watching the rest of their family hugging one another and the police and random journalists in the audience. Imogen was feeling something she hadn’t felt in a long time: a fierce, bitter love for them all. Suddenly, she realized why it was so hard to picture herself at Lilyworth: Her family wouldn’t be there.

I’m going to miss them, she admitted to herself. I’m going to miss them so much.

IMOGEN SAT IN the kitchen the next morning, sipping a cup of tea, listening to the ticking of the cuckoo clock that Aunt Bets had stolen from an old people’s home. She couldn’t hear screaming children or illegal gambling or any of the noises she usually heard when the other Crims were awake, because the other Crims were very much asleep. Everyone had stayed up very late the night before—a lot of warm champagne had been drunk, a lot of out-of-tune songs had been sung, a lot of misguided text messages had been sent. Luckily, Josephine had accidentally sent Imogen the text she’d intended for PC Donnelly, confessing to the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888 and claiming to look “very good in a top hat.”

Imogen smiled as she thought about the previous night. She and Delia had stayed up chatting for hours, doing impressions of the other Crims and making fun of each other and generally remembering why they had been such good friends in the first place. She had told Delia all about Lilyworth, and Delia had admitted that it actually sounded like fun—and then Delia had forced Imogen to listen to a Kitty Penguin song over and over again until Imogen actually found herself liking it. A bit.

But the best thing had been watching her family together—her mother and father waltzing, gazing into each other’s eyes, Uncle Clyde and Uncle Knuckles doing ill-advised arm wrestles (Uncle Clyde had to lie down on the floor for a while until he had enough energy to stand up), and Henry and the twins teaching Aunt Bets to beatbox. She turned out to be a natural. The evening had reminded Imogen of all the nights she had stayed up late with the grown-ups when she was little, feeling so proud to be a Crim. The only trouble was, everyone being together again made her miss Big Nana more than ever. But Imogen shook that thought off. Her family was out of jail, and Jack Wooster had his lunch box back. Everything was all right.

Everything was more than all right, actually, Imogen thought as she opened her laptop and reread the email she’d received from Ms. Gruner that morning:

Dear Miss Crim,

As it appears that your family was wrongly accused, we will be happy to restore your place at Lilyworth Ladies’ College, effective immediately—

“Morning, Imogen.” Imogen looked up to see Delia standing in the kitchen doorway, wearing her Kitty Penguin pajamas. “Aren’t you going to make me a cup of tea?” said Delia—and then she noticed Imogen’s luggage piled up neatly in the front hallway. She stared at Imogen, openmouthed with outrage. “No way. You’re not leaving, are you? You can’t!”

Imogen looked away. She had been dreading this moment. She knew Delia would make fun of her for still caring about Lilyworth, but she did care—just like Delia cared about taking selfies in inappropriate places and getting her thefts featured in Teen Shoplifter magazine. The election for head girl was only two days away. Imogen had booked a train ticket back to school for that afternoon. It was too late to change her mind now. “I’m sorry, Delia,” she said, shaking her head. “I have to go.”

Delia crossed her arms. “You don’t have to go. We’ve been having fun together, haven’t we? It’s been just like things used to be before you forgot who you were and got all stuck-up and started caring about obeying the law.”

Imogen sighed. “Look—” she started.

But then the doorbell went. Imogen jumped up to answer it, grateful for the distraction.

“Willkommen, bienvenue,” sang Big Nana’s voice from the doorbell.

Delia followed Imogen into the hallway, arms still crossed. “What would Big Nana think of you abandoning us again?” asked Delia.

Imogen didn’t want to think about that right now. She didn’t want to think about the hurt in Delia’s voice, either. Or how much it hurt her to think about leaving her family again. So she ignored Delia and opened the door—and there, on the doorstep, stood Mrs. Teakettle, adjusting her little velvet hat on her curly gray hair.

Imogen smiled at her warily. Mrs. Teakettle looked so innocent and so unlike a Kruk. But as Uncle Knuckles’s fondness for tiny kittens and hatred of violence proved, appearances can be deceiving. . . .

“Hello, my dear!” said Mrs. Teakettle. “Are the children dressed yet? We’re going on a lovely nature hike today! I’m going to teach them the names of all the different trees in Blandington—the plane tree and the beech tree. That’s it. Blandington doesn’t have much wildlife diversity, have you noticed?”

“Oh,” Imogen said uncomfortably. “You must not have seen the news. . . .”

“The news? Has something happened? Is everyone okay? I can’t bear the news these days—all that terrible crime!”

“Everything’s fine,” Delia said quickly. “It’s just that our family has come home. From their . . . travels.”

“Well, how wonderful!” said Mrs. Teakettle. “Remind me where they went?”

Imogen started to say “Thailand” at the same time that Delia said “Cuba.”

“Thailand and Cuba? Goodness!” said Mrs. Teakettle, raising her eyebrows.

“Yes . . . they all decided to see the world before they retired,” said Imogen, glancing at Delia.

“You have a family business, don’t you?” said Mrs. Teakettle. “What is it again?”

“Hat making,” said Imogen, at the same time Delia said, “Taxidermy.”

“Hat making and taxidermy? How niche!” said Mrs. Teakettle.

“Yes,” said Imogen. “We specialize in stuffing people’s pets and then making little outfits for them. We’re very popular on Etsy.”

“Stop talking,” Delia hissed in her ear.

Imogen stopped talking. Then she smiled apologetically at Mrs. Teakettle and said, “I’m sorry we didn’t let you know sooner. Now that everyone is back, we won’t need you to babysit the children anymore.”

She braced herself. How would Mrs. Teakettle react? She wished Freddie were here as backup, but he was back in his illegal gambling den.

But Mrs. Teakettle just gave Imogen and Delia a sad little smile and said, “Oh, that’s such a shame! They are such darlings, and so well behaved. They loved my reading bedtime stories to them—their favorite was Hard Times by Charles Dickens. Such an uplifting book, that one. Isn’t it, Delia, dear?”

Delia nodded. “Whenever I’ve had a bad day, I think, At least I haven’t died falling down a mineshaft like Stephen from Hard Times. That always cheers me up.”

Imogen tried not to let the relief she felt show on her face. “I promise that if we ever do need a babysitter, you’ll be the first person we’ll call,” said Imogen.

“Thank you,” said Mrs. Teakettle, squeezing her hand.

“Thank you,” said Delia.

“Well,” said Mrs. Teakettle, “if I’m not needed here, I suppose I’d better get home.” She nodded to them both and opened the front door.

I must have been wrong about Mrs. Teakettle, Imogen thought as Mrs. Teakettle stepped onto the front path. She’s harmless—she can’t be a Kruk. But there was still the matter of the song. . . . “Mrs. Teakettle?” Imogen asked.

“Yes, dear?” said Mrs. Teakettle, turning around.

“You know that song you taught the children? Did you make it up?”

Mrs. Teakettle nodded. “I was quite proud of that one. I’ve always wanted to write a song that rhymed ‘judge’ and ‘grudge.’ Why?”

Imogen hesitated. But Mrs. Teakettle was being so reasonable—surely it couldn’t hurt to ask? “Well . . .

I was in London the other day, and I heard another family singing another version of the same song.”

Imogen studied Mrs. Teakettle’s face for a reaction. But Mrs. Teakettle’s crinkly smile did not waver for a second.

“Oh—do you mean the Kruk family?” Mrs. Teakettle said airily. “I babysit the Kruk children, too, sometimes.”

Imogen and Delia looked at each other. Mrs. Teakettle didn’t seem to have a problem admitting this at all. So she couldn’t have been sent to spy on them. Could she?

“Isn’t it annoying having to go all the way to London to look after them?” asked Imogen. “Over an hour on the train, there and back . . .”

“Oh, I don’t mind that,” said Mrs. Teakettle. “I’m an old friend of the family. Met them when I was a little girl. I hear they have a bit of a reputation in the press, but you shouldn’t believe all of that—they’re really lovely people when you get to know them, especially the children. Little darlings!” Her smile hardened a little, the way cupcake frosting does if you don’t eat it quickly enough. “Why?” she asked. “Is that a problem?”

“No!” said Imogen, her voice slightly too high-pitched. Was it really just a coincidence that Mrs. Teakettle babysat for two families that made their business in crime? Imogen shook the thought away. It didn’t matter now, anyway, even if Mrs. Teakettle was a Kruk. She wouldn’t be looking after the Horrible Children anymore.

“Well, then, my dears,” said Mrs. Teakettle. “I suppose this is good-bye.”

“We’ll really miss you,” said Delia.

“Come here, both of you,” said Mrs. Teakettle, and she pulled Imogen and Delia into a hug. “I’ll miss you, too,” she said.

And then she gasped and took a sudden step backward.

She was looking at something behind Imogen and Delia, in the hallway.

Imogen turned around—Mrs. Teakettle was staring at Big Nana’s soft toy hippo, which was sitting by her luggage. She had decided to take it back to school with her.

“Where did you get that?” Mrs. Teakettle asked, pointing at the hippo. Her voice was several octaves lower than usual, and gravelly. It sounded . . . familiar.

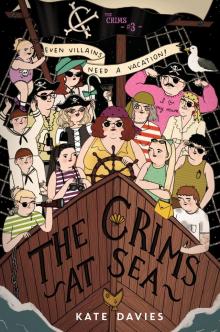

The Crims #3

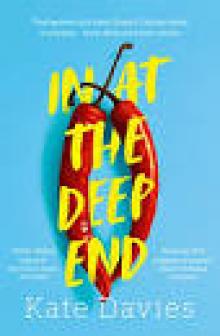

The Crims #3 In at the Deep End

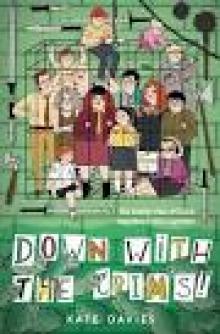

In at the Deep End The Crims #2

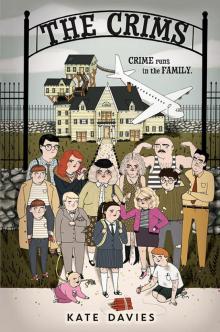

The Crims #2 The Crims

The Crims Take a Chance on Me: Lessons, Book 4

Take a Chance on Me: Lessons, Book 4